Allow me to suggest to my fellow Catholic sacred artists a “canon” of ten fundamental propositions. These ideas and proposals are my personal musings. They assist me in organizing my thoughts and behavior. It is my hope that they will act as an organizational tool for the interested reader, too. They may also assist you, as they have for me, in providing clarity to our foundation and purpose as sacred artists.

The term “Catholic” in this document refers to the Latin Rite (Rome) and the more than twenty Rites of the Eastern Rite Catholic Churches that are in union with Rome. Sacred artists within the Orthodox Rites and the Protestant denominations may also find some of the proposals helpful in their work.

The use of the term “canon” refers to the the original Greek word, kanon, which indicates a “model” or “standard.” My suggestion is that the following “canon” acts as a “model” for the sacred artist since this is the first in-depth publication of my thoughts on this subject and there is no consensus by the Catholic sacred art community as to its acceptance by a majority of artists and commentators in the field. Consensus may or may not be achieved in the future. Please consider these thoughts as a beginning, a starting point.

This post is a revision of a previous post in March 2017 with a similar theme. Also, as mentioned earlier, I will eventually discuss the spiritual and artistic values of Beato Fra Angelico (Guido di Pietro – Fra Giovanni da Fiesole, 1395 – 1455). I would be remiss if I did not say that he was my model for this post. I perceive Fra Angelico as being an artistic and spiritual giant of Latin Rite art who exemplified, in his behavior and sacred art, many of the ideas found in the “Canon” below.

The reader should also view the Explanatory Notes that follow the ten propositions to obtain commentary. I have provided a list (which is also a starting point) of five organizations in the Explanatory Notes below to assist you in your own studies. If you are aware of other organizations or Catholic colleges that promote the sacred arts, please contact me with that information. You are invited to reflect on these ideas in the Comments Section or, if you wish, send me a private email at deaconiacono@icloud.com.

The Canon of a Catholic Sacred Artist

1) The Latin Rite, and the more than twenty other Rites of the Catholic Church that are in union with Rome, have a traditional foundation: Sacred Scripture, Sacred Tradition, and the dogmas and doctrines of the Church. This foundation ultimately impacts the Catholic sacred artist within a specific cultural tradition. Catholic sacred artists accept and believe in this foundation.

2) A Catholic sacred artist’s first priority is to develop his or her personal holiness in light of the prayer and Sacramental traditions of our Church; specifically, worship through attendance at the sacred liturgy of the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass, reception of the Sacraments, and liturgical prayer – through the Liturgy of the Hours and/or sacred music.

3) A Catholic sacred artist understands the value of the Adoration of the Eucharistic Face of Christ (the true icon). Eucharistic Adoration is necessary, and highly recommended, because it is based on the artist’s desire for friendship with Jesus Christ, the need to express that friendship in an act of praise and thanksgiving, and Jesus’ desire for friendship with the artist. Within that prayer form, which requires the development of interior silence and stillness of soul, the sacred artist receives inspiration and solace. Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI has reminded us in his book The Spirit of the Liturgy (Ignatius Press, page 90) that “Communion only reaches its true depth when it is supported and surrounded by adoration.” The word “adoration” is used because we are acknowledging the Real Presence of the Body, Blood, Soul, and Divinity of Jesus Christ in the Eucharist.

4) Creativity within Catholic sacred art is influenced by many ideas, the foremost being the expression of the truth, goodness, and beauty of God. The creativity of the sacred artist should always be disciplined by the truth that the artistic product must be able to be clearly understood by the viewer or listener so that it may aid their worship and veneration of God, His saints, and angels.

5) Catholic sacred art brings artistic life to Christ’s Gospel message and the witness of the historic and spiritual personalities of the Church. Sacred art, in all its various forms, contributes to the New Evangelization of the Catholic Church.

6) Catholic sacred art can be a sacramental if it conforms to the aesthetic, semantic, and theological principles of our Faith.

7) Catholic sacred artists believe that the Sacramental grace of God strengthens personal faith and allows them to become co-creators of artistic beauty. The artist becomes a co-creator when he/she attempts to make a beautiful artifact and ensures that the attributes of the artifact are truthful, good, and beautiful. For the Catholic artist, God is the source of all beauty, truth, and goodness.

8) Catholic sacred art is a critical part of the liturgical work and prayer of the Catholic Church. An artist’s creative act of making their art form, and the finished product, is not just art; it is communion with God. Sacred art, therefore, is a cultural artifact that turns our heart, mind and soul towards God in praise, penance, petition, and thanksgiving,

9) Catholic sacred art enhances the sacred liturgy of the Church, and may make a significant contribution to the praise, thanksgiving, and repentance of the viewer or listener.

10) Catholic sacred artists are willing to continually learn not only about their Faith and Church traditions, but to professionally grow by increasing their awareness of developments within Catholic sacred arts, its present day contributors, networking and sharing ideas, and continually improving their personal artistic techniques within their artistic discipline.

Explanatory notes – the numbers below correspond to the number of the specific statement above

1) Culture is the fundamental engine that propels history; and the foundation stones of any culture is its Faith. An acceptance of the importance of a faith tradition (and tolerance of other faith traditions) by the people of a nation or continent significantly contributes to the growth of its inhabitants; rejection of the role of faith has shown that a culture will be stunted and eventually collapse. Within a culture that is growing in a positive manner there is the belief in a critical idea: tradition. This idea applies to faith and religious systems, political life, scientific exploration (such as the scientific method), the arts, etc. Tradition, however, is not an idea that is, in its application, suffocating to an individual’s growth or creativity. Positive change can certainly occur within a culture that follows specific traditions.

Briefly let us apply this word, tradition, to the Rites of the Catholic Church. A Rite represents a church tradition about how the Holy Sacraments are to be celebrated. There are over 23 Rites within the Catholic Church, of which the Latin Rite (Roman Catholic) is the largest with over 1.5 billion members. The other 23 Eastern Catholic Rites are in union with Rome, however, the Greek and Russian Orthodox Churches, have not been in union with Rome since the 11th century.

Faith in Jesus Christ and the Nicene Creed has been the mortar between the foundation stones of every culture of Eastern and Western Europe for millennia and for hundreds of years in the Americas. Our Faith and its religious tradition must be viewed in two ways: a small “t” relating to cultural norms of behavior within our specific Rite, and, a capital “T” referring to Church Tradition. This idea of Sacred Tradition was specified by Jesus Christ, the Apostles, the Fathers of the Church, and the many hierarchical pronouncements proclaimed by Ecumenical Councils and Popes (such as the Nicene Creed, or the 7th Ecumenical Council and its promotion of sacred icons). This understanding is in association with the teaching authority (the Magisterium) of the Latin Rite of the Catholic Church and Eastern Catholic Rites that are in union with Rome.

Colin B. Donovan, STL informs us (confer EWTN website) that when we consider the transmission of faith we must acknowledge that historically there are three major groupings of Rites: Roman, the Antiochian (Syria) and the Alexandrian (Egypt). The Byzantine Rite, the fourth major Rite, developed out of the Antiochian. These various Rites came into existence because the Apostolic ministry, within different cultural centers of the Roman Empire, ultimately saw the elements of the Faith being “clothed in the symbols and trappings” of a particular culture. This was promoted because the One, Holy, Catholic, and Apostolic Faith required that the Church become “all things to all men so that some might be saved” (see First Corinthians 9:22).

Historically, the four major Rites ultimately gave birth to over 20 liturgical Rites that currently exist, are in union with Rome, and to this day are serving the faithful. Applying this idea we can say that it is incumbent upon sacred artists within these Rites to ensure that their art provides a clear, unambiguous message to the world (in relation to the “t” and “T” of tradition). This demands faith, loyalty, and trust by the artist in Jesus Christ and the truths of the Church.

2) Rev. Deacon Lawrence Klimecki from Pontifex University has written insightfully on his blog about creativity, beauty, the role of the artist, and sacred art. He asks an important question: “What is sacred art? Is it liturgical art? Devotional art? Art with religious themes? The Catholic artist must address the issue of “who” is the audience? What purpose and need is the “sacred” artist trying to meet” in their creative act of making art, architecture, music, poetry, drama, or literature? In trying to answer Deacon Klimecki’s valuable questions we may begin by saying that the term sacred, from the Catholic Church’s cultural point-of-view, is any idea or artifact that refers to, and makes visible (if possible) the truth, goodness, and beauty of God, His saints, and angels. It also critically assists in a person’s worship of God and veneration of His angels and saints. Sacred artistic artifacts convey or represent the dogmas, doctrines, artistic styles within a specific time period, and the historic personalities of the Faith.

Sacred art, in all its various forms (architecture, painting, sculpture, stained glass, illuminated manuscripts, metalworking, music, etc) are the visual and auditory means through which we are assisted in our desire, through our soul, intellect, and senses, to be in union with the all knowing, all powerful, and beautiful God of Sacred Scripture and Tradition. Sacred art, therefore, is a cultural artifact that turns our heart, mind and soul towards God in praise, penance, petition, and thanksgiving,

Catholic sacred artists undertake a great spiritual responsibility. This responsibility requires that the artist be firmly rooted in faith, the reception of the Holy Sacraments (especially Reconciliation and Holy Eucharist), and personal and liturgical prayer. Besides Eucharistic Adoration, some prayer aids for sacred artists would be participating in sacred music and/or praying the Liturgy of the Hours (Divine Office) either alone or in a group.

3) Saint John Paul 2, in note 61 of his encyclical Ecclesia de Eucharistia (The Church Comes from the Eucharist) explains that “By giving the Eucharist the prominence it deserves, and by being careful not to diminish any of its dimensions or demands, we show that we are truly conscious of the greatness of this gift. We are urged to do so by an uninterrupted tradition, which from the first centuries on has found the Christian community ever vigilant in guarding this ‘treasure.’ Inspired by love, the Church is anxious to hand on to future generations of Christians, without loss, her faith and teaching with regard to the mystery of the Eucharist. There can be no danger of excess in our care for this mystery, for “in this sacrament is recapitulated the whole mystery of our salvation.”

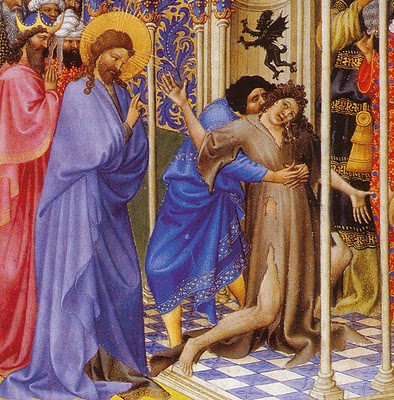

What is prayer? The saints tell us that prayer is the turning of the heart toward Our Lord, His Blessed Mother, the angels and the saints and allowing our mind and heart to sincerely speak words of love, praise, thanksgiving, and repentance to them. The sacred artist enters into communion with the Heavenly Court through the union of their prayer with creativity. This communion comforts and assists the sacred artist in their work. Unity allows a sacred artist to walk the various paths of Holy Scripture and experience the moment that the Scripture, or a story of the saints, presents to the soul. This experience feeds and transforms the sacred artist by affecting the clarity, line, form, and colors of their art (a tip-of-the-hat to my friend and teacher Dr. George Kordis and his seminal work on line, color, and form). This may also be how Beato Fra Angelico experienced the Crucifixion, and according to Vasari, as he painted he wept over the enormity of Christ’s sacrifice. In this process Fra Angelico prefigures Ignatius of Loyola by about 125 years in the ability to experience the words of Holy Scripture within his imagination. The use of the word – “imagination” – does not mean or imply “fantasy,” nor does the person in prayer “make-up” images not found in the Gospels or Church history. St. Andrei Rublev, Beato Fra Angelico, St. Ignatius of Loyola and others utilized this type of prayer experience to affect their work.

4) While remaining loyal to Sacred Tradition, the Church’s artistic tradition is fluid and is always affected by the artist’s creativity and understanding. This may lead to new styles and interpretations of artistic expression. These new expressions, however, are never vulgar or disrespectful, and will provide no confusion as to the meaning of the images within the art form. Sacred art, while not exclusively catechetical, does certainly play a role in the catechesis of the faithful.

5) Also, the Western Rite, and the Eastern Rites, affirm that preaching the Gospel message through (word, service (Spiritual and Corporal Works of Mercy, and sacred art), and celebrating the Holy Sacraments is critical for the evangelization, spiritual health, and salvation of God’s people.

6) Icons, sacred images, woodcarvings, calligraphy and other sacred arts if based on the Holy Gospels and Church Tradition spread the Good News of the Gospel. The sacred arts are sacramentals when they point the way to God. Sacramentals are blessings. The seven Sacraments provide the grace that interiorly heal and nourish us. Sacramentals, however, assist us in the exterior visualization of Our Lord Jesus who made that process possible through His Incarnation and Redemption of humanity. It also assists us in the visualization of His angels and especially His Blessed Mother and the saints, who modeled Jesus in their own lives.

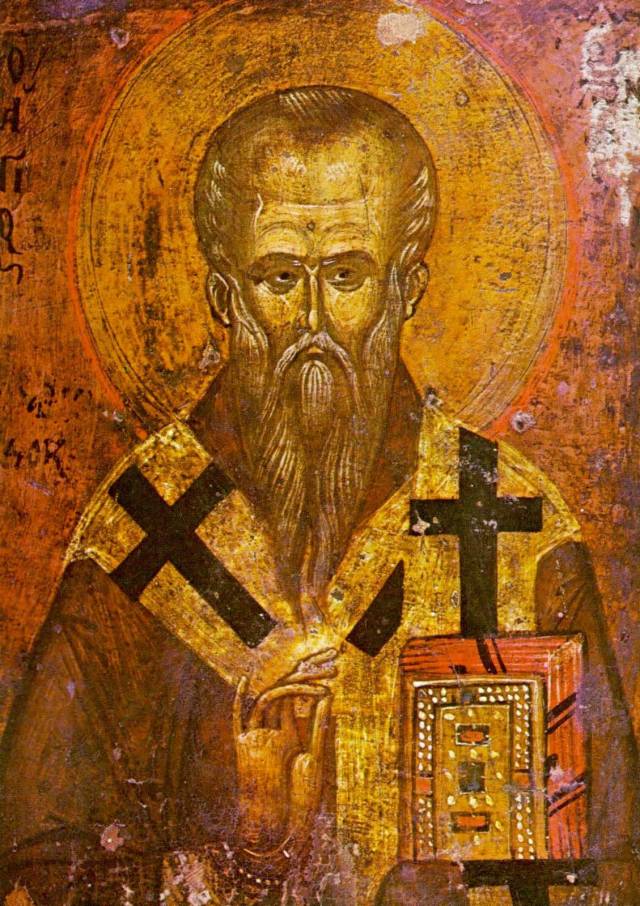

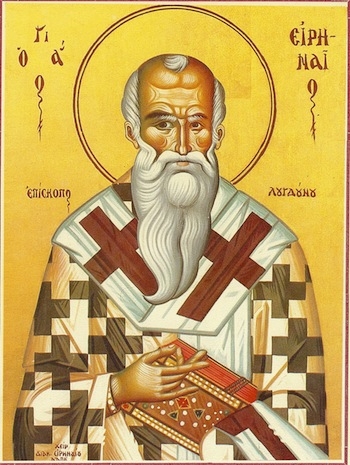

An icon is a sacred image (confer John 1:14). An iconographer follows specific traditions of craftsmanship and specific elements of Theological (Scriptural and dogmatic content), Semantic (the visual language of the icon, appropriate perspective, the use of light, line, and color to create form, and correct use of signs and symbols within the icon), and Aesthetic principles (the quality of beauty with the icon itself). These three principles are based upon the sacred Tradition of the Church. The history of the Western and Eastern Rites illustrates that the sacred artist has continually moved through different artistic periods and technical understanding. Within sacred art artistic styles change (this may be a good thing), but the truth of the Faith, and the witness of the Church’s spiritual giants – the witness of Jesus Christ and His saints – cannot.

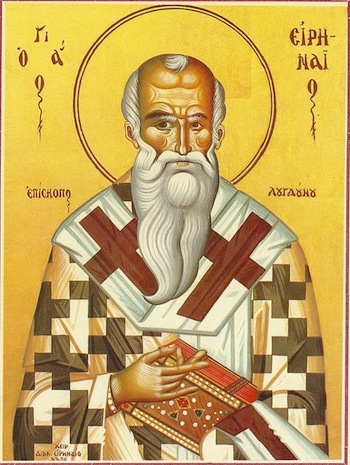

David Clayton, Provost at Pontifex University, has pointed out that we need to remember and apply the two ideas of St. Theodore the Studite (AD 759-826) in his criteria which must be followed if an icon is to be considered a sacramental, thus, worthy of veneration: 1) The icon must display the title of the saint or feast day represented, and, 2) the image needs to display the essential physical characteristics and attributes of the saint represented, such as keys for St. Peter; a book of Scriptures, a bald head, or sword for St. Paul; dalmatics, the Book of the Gospels, or thuribles, for deacons; or the gaunt figure of St. Mary of Egypt, etc.. Each angel or saint has a specific name and attributes.

The Roman Catholic Church moved out of an Iconographic period into the Gothic period, and then into the Baroque period. The Greek and Russian Orthodox Church and many of the Eastern Catholic Churches in union with Rome stayed within the period of Iconography that developed out of the early centuries of the Church. Cultural conditions (such as geographical location, political influence, and the affect of the Western European Enlightenment in the 17th and 18th centuries), access to earth pigments, artistic differences and changes in style all affected the Iconographic period within the Eastern Rite of the Church.

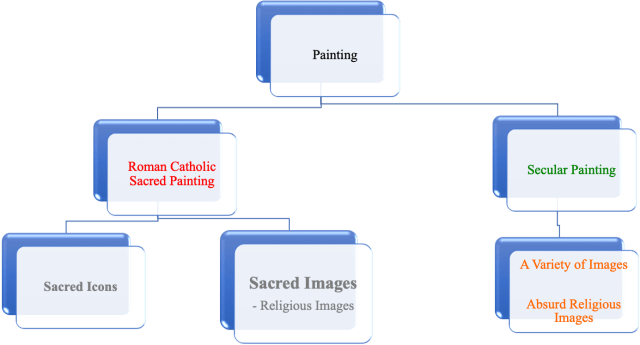

It is important to note that within the Latin Rite a sacred image is a religious image that is created of a historical holy person or religious scene; however, the artist allows their full creativity and personal interpretation to enter into the craftsmanship and artistic process (an example being Michaelangelo’s Sistine Chapel).

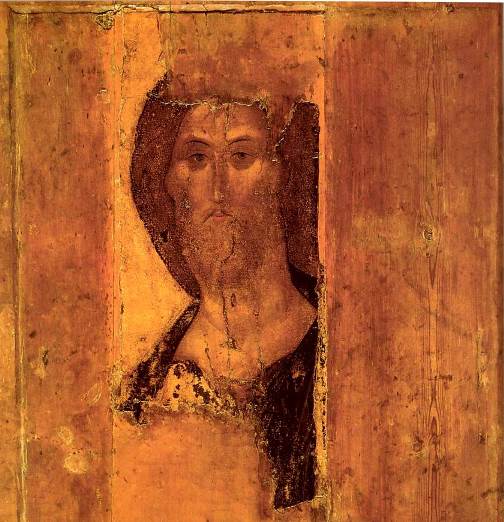

Historically, personal creativity and technique, and the change of specific artistic styles are present within Eastern Rite iconography. Their sacred icons are affected by the culture, historical moment, style, and geographical location of the artist (examples being Coptic vs. Greek, or, Novgorod vs. Moscow). The Eastern Rites, those that are in union with Rome, and those that are not, believe that the sacred icon must be faithful to Sacred Scripture, historic reality, and the Traditions the Church. The icon’s meaning must be easily recognizable by the viewer. The artistic style may change but there is no room for personal interpretation to change the way Christ, His angels, or saints are portrayed (an example of this would be portraying Christ as doing some action outside the truth and witness of the Gospels, or having Him beheaded rather than crucified). Sacred icons should never be static and “flat.” The personality of the sacred artist is present in their art, and yet, that is not the most important issue.

A sacred icon is made in a specific manner. The techniques of production (from type of board to board preparation, drawing of the image, the necessity of line giving form to color – “its logos” as discussed by one of my teachers, George Kordis, the type of perspective, the predominant use of egg tempera and natural materials – earths and minerals, the lack of symmetry, moving from dark colors to light, and the final blessing by a priest or deacon) are taken seriously by the Orthodox and Eastern Rite Churches. It is my opinion that if a Latin Rite artist decides to paint a sacred icon, out of respect, they should study and follow the traditions of the Eastern Catholic Rites and the Orthodox Church. This can be accomplished by either studying with their iconographers or with Roman Catholics who have studied with them and follow their traditions of iconography.

I do believe that a Latin Rite sacred artist may paint a religious image in the style of a sacred icon, but, must be careful to explain the difference between the two types of representation. I currently follow this methodology of differentiating a sacred image (religious art) from a sacred icon, and, religious art painted in the style of a sacred icon. My basis for this is respect for the Orthodox and Eastern Rite traditions and how they view their sacred art forms. Yet, it must be admitted that the “traditions” of Orthodox sacred art were primarily formalized by the Greek artist Photis Kontoglou (1895-1965), and the Russian artist and historian Leonid Ouspensky (1902-1987). Thus, these two scholars, within the last one hundred years, outlined what they believed was the historic “tradition” of Orthodox painting, and this “tradition” became formalized within the Orthodox community. A Catholic artist from another Rite, or within the Latin Rite, may not be concerned with these issues. I believe, however, that the Latin Rite sacred artist must not only be aware of the currents within the Orthodox sacred art community but be respectful of it, too.

In his book Spirit of the Liturgy, Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI provides a wonderful overview of the three periods of sacred art within the Roman Catholic Church (Iconographic, Gothic, and Baroque). You will notice that even though he discusses the Renaissance he does not include it within the three traditions. High Renaissance artists were not inspired purely by prayer or catechesis in the production of their art. For many their motivation was the desire to please themselves, their patrons, or the profit motive. Renaissance sacred images do have spiritual value and some can motivate the viewer to prayer and communion with God.

An example of an icon is St. Andrei Rublev’s image of Christ, or his icon of the Holy Trinity. An example of a sacred image is Pietro Annigoni’s image of St. Joseph and the Child Jesus in Joseph’s workshop, or Masaccio’s Holy Trinity. A sacred image painted in the style of an icon is my rendition of St. Michael Holding the Holy Eucharist. Pictures of these icons and images are found below.

7) The attributes of the sacred artifacts are beautiful. These attributes conform to the three basic elements of beauty as defined in the writings of St. Thomas Aquinas: clarity – the listener or viewer can discern what the artifact is, what it means, and that it reflects a “radiance” to those who perceive it; proportion – the listener or viewer can discern the artifact’s unity, order, harmony, and the correct relationship of its individual parts; and integrity – the listener or viewer is able to understand the “wholeness” of the artifact. Is beauty in the eye of the beholder? Certainly it is affected by the individual’s culture, geographical location, historic period, and other issues; but, we can also say that it is objective, in that people of Faith do not deny the Truth, Goodness, and Beauty of God.

Within the Roman Catholic Church and the Eastern Churches, it is believed that “Our justification comes from the grace of God which was merited for us by the Passion, Death, and Resurrection of Jesus Christ.” Sacramental Grace is a participation in the life of God. Justification is conferred through the Sacramental grace of Baptism. “Grace is the free and undeserved help that God gives us to respond to His call to become [members of His family], children of God, adoptive sons and daughters, partakers [through the Holy Sacraments] of the divine nature and eternal life” (confer John 1:12-18; 17:3; Romans 8: 14-17; 2 Peter 1:3-4). As the Council of Trent teaches – grace is known by faith – and faith, in association with the gifts and fruits of the Holy Spirit, produce good works. Our Lord teaches in Matthew 7: 20 “You will know them by their fruits” (confer Catechism of the Catholic Church, 2nd edition, paragraphs 1987 through 2005).

8) Contemporary Greek artist and iconographer, Dr. George Kordis, writes of this principle in his book Icon As Communion. Numerous authors have written in this field, to name a few, with the titles of their books: Sister Wendy Beckett’s Real Presence, Meditations on the Mysteries of Our Faith, and Encounters With God; Paul Evdokimov’s The Art of the Icon; David Clayton’s The Way of Beauty: Liturgy, Education, and Inspiration; John Saward’s The Beauty of Holiness and the Holiness of Beauty; Christoph Cardinal Schonborn’s God’s Human Face; Jem Sullivan’s The Beauty of Faith; Monsignor Timothy Verdon’s Art and Prayer; and Jeana Visel, OSB, Icons in the Western Church.

9) In the Roman Catholic Church, liturgy as defined in the New Testament, “refers not only to the celebration of divine worship but also to the proclamation of the Gospel and to active charity” (confer Luke 1:23; Acts 13:2; Romans 15:16, 27; 2 Corinthians 9:12; Philippians 2: 14-17, 25, 30. Also, review the Catechism of the Catholic Church, 2nd edition, paragraphs 1066 through 1209).

The work of a sacred artist (this of course includes all the sacred arts) can be viewed as a liturgical act because it provides a service to our neighbor, in that the sacred art elucidates and visualizes the reality of the truth, goodness, and beauty of God. The sacred artist assists the Church in making the reality of Christ present within the community of believers. Sacred artists, by providing this service, are participants in active charity. They aid in providing a “visible sign of communion in Christ between God and men” (confer paragraph 1071, Catechism of the Catholic Church, 2nd edition).

10) Transformation in Christ is a Sacramental, prayerful, intellectual, and fellowship process. A Catholic sacred artist must be involved in all four of these transformative elements in order to reach their full potential. A student of this process would be remiss if they did not investigate the writings of St. Thomas Aquinas and St. Augustine on these issues. St. Augustine writes beautifully in his Confessions on the truth and the beauty of God, one paragraph begins: “Late have I loved you, O Beauty ever ancient, ever new, late have I loved you”…. Artists are wise to remember that their art must not only be good and truthful in its message, but beautiful as well because they are reflecting the truth, goodness, and beauty of God Himself.

Catholic sacred artists, as they study the various manifestations of sacred art over the last two millennia, should network and become aware of the contributions of contemporary leaders and contributors in the various fields of Catholic sacred art. The Catholic Art Guild, The Catholic Artists Society, The Foundation for Sacred Arts, and the Institute of Catholic Culture are organizations to help you discover contemporary issues in Catholic sacred art; they also occasionally provide seminars and lectures in sacred art. Pontifex University, an on-line Master of Arts Degree program in Roman Catholic sacred art, is also another opportunity for a sacred artist or student who desires to advance their knowledge and understanding of sacred art.

Some of the recent Popes have expressed valuable insights on beauty, sacred art, and the role of the sacred artist. A few examples: the many writings of Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI such as, his 2008 homily in St. Patrick’s Cathedral in which he discussed the architecture and stained glass windows of St. Patrick’s as a quest for truth and faith; his Meeting With Artists in November 2009, his 2002 comments “The Feeling of Things: The Contemplation of Beauty,” and his book The Spirit of the Liturgy. Professor Matthew Ramage’s January 2015 essay “Pope Benedict XVI’s Theology of Beauty and The New Evangelization” (found in Homiletic and Pastoral Review), is an excellent introduction to Pope Benedict XVI”s contributions to truth and beauty in sacred art.

Emphasis must also be placed on the absolutely critical document for any sacred artist: Pope Saint St. John Paul II’s Letter to Artists. Pope Pius XII’s 1947 encyclical, Mediator Dei, from a liturgical point-of-view it explains in paragraph 187 that “Three characteristics of which our predecessor Pope Pius Xth spoke should adorn all liturgical services: sacredness, which abhors any profane influence; nobility, which true and genuine arts should serve and foster; and universality, which, while safeguarding local and legitimate custom, reveals the catholic unity of the Church” (Pius XII referenced this from an Apostolic Letter of Pope Pius X of November 1903). These three principles, when united with the principles of aesthetic, semantic, and theological truth, provide the Catholic sacred artist with a firm foundation on which to build their creative work.

Thank you for reading this and I look forward to your comments. Please see the images below, too.

Pax Christi, Deacon Paul O. Iacono

Originally posted April 2, 2018; updated June 2, 2018

Fra Angelico Institute for Sacred Art.

Copyright © 2011- 2018 Deacon Paul O. Iacono All Rights Reserved

Images:

St. Andrei Rublev’s icons: Christ (completed 1410, above) and his The Trinity (1411, or 1425-27)

Masaccio’s sacred image: Holy Trinity (completed 1428, above) and

Pietro Annigoni’s sacred image: St. Joseph the Worker (altarpiece, completed 1963, below)

Deacon Paul O. Iacono’s sacred image done in the style of an icon: of St. Michael Holding the Holy Eucharist, (completed 2015-2017). Please see my post on this blog of September 29, 2017 for a brief explanation.

My text/last photo, Copyright © 2011- 2018 Deacon Paul O. Iacono All Rights Reserved

The above photo is one of the thirty-six panels describing events of the New Testament, in this case the Coming of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost. Notice Jesus’ mother Mary at the top center of the image with the Apostles and disciples (Peter is on her top right, and John is on her top left). They are receiving the Gifts and Fruits of the Holy Spirit symbolized by the tongues of fire. A curious crowd gathers below the upper room as described in the Acts of the Apostles.

The above photo is one of the thirty-six panels describing events of the New Testament, in this case the Coming of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost. Notice Jesus’ mother Mary at the top center of the image with the Apostles and disciples (Peter is on her top right, and John is on her top left). They are receiving the Gifts and Fruits of the Holy Spirit symbolized by the tongues of fire. A curious crowd gathers below the upper room as described in the Acts of the Apostles.

You must be logged in to post a comment.